The so-called oracle bone inscriptions (jiaguwen 甲骨文 "plastron bone inscriptions") are remnants of archival documents from the late Shang period 商 (17th-11th cent. BCE), upon which records of royal divinations were carved or inscribed. The material is the plastrons (breast shields, gui fujia 龜腹甲) of tortoises or scapulae (shoulder-blades shou jiagu 獸胛骨) of different cattle. The oracle bone inscriptions are the oldest extant Chinese texts written in a perfectly developed script. Unfortunately, no older stages of the Chinese script are preserved (except for some clan insignia and examples of logographs of uncertain meaning), but it appears in full maturity on the Shang oracle inscriptions.

Wang Yirong 王懿榮 (1845-1900), a late Qing-period 清 (1644-1911) expert on bronze inscriptions, was the first to recognise that the inscriptions written on bones sold by drugstores as medicine were of an ancient date. From 1899 onwards, he collected numerous such inscriptions.

His findings instigated numerous other scholars to collect such bones as well. Among these researchers were Wang Xiang 王襄 (1876-1965), Meng Dingsheng 孟定生 (1867-1939), Liu E 劉鶚 (1857-1909), Luo Zhenyu 羅振玉 (1866-1940), the American Frank Herring Chalfant (1862-1914, Chinese name: Fang Falian 方法斂), the Britons Samuel Couling (1859-1922, Ku Shouling 庫壽齡) and Lionel C. Hopkins (1854-1952, Jin Zhang 金璋) as well as the Japanese Hayashi Taisuke 林泰輔 (1954-1922).

From 1928 to 1937, the Institute of History and Language of the Academia Sinica (Zhongguo yanjiuyuan Lishi yuyan yanjiusuo 中國研究院歷史語言研究所) carried out 15 excavation campaigns on the site of the ancient capital of the Shang, the so-called "Ruins of Yin" (Yinxu 殷墟) near Anyang 安陽, Henan. They dug out 25,000 pieces of oracle bones. In 1973, the Archaeological Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Yuan Kaogu Yanjiusuo 中國社會科學院考古研究所) launched an excavation campaign in the village of Xiaotun 小屯 near the Yinxu site. During the 1950s, more oracle bones were excavated in Zhengzhou 鄭州, Henan, the site of the royal capital in the mid-Shang period. Excavation sites of minor importance were Hongdong 洪洞 in Shanxi, Changping 昌平 near Beijing, Fenghao 豐鎬 in Shaanxi, as well as other places of the early history of the Zhou dynasty nearby.

Until now, more than 150,000 pieces of oracle bones have been excavated and can be found in various museums and archives around the world. The findings have been largely published. The most significant printed collections are:

| 鐵雲藏龜 | Tieyun canggui | 劉鶚 Liu E (1903) |

| 殷墟書契 | Yinxu shuqi | 羅振玉 Luo Zhenyu (1913) |

| 殷墟卜辭 | Yinxu buci | James Mellon Menzies (Ming Yishi 明義士; 1917) |

| 龜甲獸骨文字 | Guijia shougu wenzi | 林泰輔 Hayashi Taisuke (1917) |

| 簠室殷契徵文 | Fushi Yinqi zhengwen | 王襄 Wang Xiang (1925) |

| 小屯第二本殷虛文字甲編圖版 | Xiaotun Di er ben Yinxu wenzi Jiabian/Yibian Tuban | 董作賓 Dong Zuobin (1948) |

| 戰後寧滬新獲甲骨集 | Zhanhou Ning-Hu xinhuo jiagu ji | 胡厚宣 Hu Houxuan (1951) |

| 戰後南北所見甲骨錄 | Zhanhou nanbei suo jian jiagu lu | 胡厚宣 Hu Houxuan (1951) |

| 戰後京津新獲甲骨錄 | Zhanhou Jing-Jin xinhuo jiagu lu | 胡厚宣 Hu Houxuan (1951) |

| 甲骨續存 | Jiagu xucun | 胡厚宣 Hu Houxuan (1955) |

| 小屯第二本殷虛文字丙編 | Xiaotun Di er ben Yinxu wenzi Bingbian | 張秉權 Zhang Bingquan (1972) |

| 小屯南地甲骨 | Xiaotun Nandi jiagu | 中國社會科學院考古研究所 Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Yuan Kaogu Yanjiusuo (1973) |

| 甲骨文合集 | Jiaguwen heji | 郭沫若 Guo Moruo, 胡厚宣 Hu Houxuan (1978-1982) |

| 小屯第二本殷墟文字乙編補遺 | Xiaotun Di er ben Yinxu wenzi Yibian buyi | 鍾柏生 Zhong Bosheng (1995) |

From the linguistic aspect, it is essential to notice that the inscriptions are written in the Chinese language and are readable and understandable if the vocabulary is known. The characters are also constructed in the same patterns as those of later date, although the shape is in many cases not that of the standard characters.

Virtually all activities of the Shang kings were recorded in the oracle bone inscriptions. For this reason, the inscriptions offer insights into the society, economy, and politics of that time. It is known how members of the royal household, both males and females, members of the aristocracy, and groups of common people were referred to; titles of the bureaucracy are known, as well as terms from the judicial system and the army. Subservient states, hostile tribes, and colonies are identified by their names—although their exact locations are not always clear. The inscriptions include records of tributes paid by these polities to the royal court, and details of the social activities the king undertook, from hunting to offerings to his ancestors. Records of human sacrifices are also preserved.

Astronomical events are likewise recorded, like eclipses or irregularities in the starry sky. The calendar was already arranged in the sexagenary cycle, as known later. Sickness and diseases are also included in the records.

All daily activities of the king were observed by supernatural beings, whether natural deities, ghosts, spirits, or the king's ancestors. All these had to be consulted to determine if a planned activity would be fortunate or if bad luck would befall the king and his entourage. Virtually the entire life of a Shang king was thus guided by prophecies from an oracle made earlier.

The method to divine by heating bones is unique to China and only a few other peoples of northern Asia. It is called scapulimancy or plastromancy. The diviners (zhenren 貞人) tried to tell the future by creating cracks (bu 卜) on the bones. Inserting a hot bronze (?) stick (therefore also called pyromancy, "divining by fire") into a hole drilled into the surface of the bones, the diviners were able to tell the future by interpreting the emerged cracks.

The Shang diviners predicted the future of sacrifices, military campaigns, tribute payments, hunting expeditions, settlement building, weather, sickness, agriculture, and childbirth — almost every aspect of daily life. In many cases, the deified ancestors of the dynasty were consulted in the simple question of whether a day was auspicious (ji 吉) or inauspicious (xiong 凶).

The most interesting thing for our knowledge about the life and religious thought of the Shang people is that they not only created cracks, but also the fact that the scribes (li 吏, shi 史) of the king wrote down the result of the divination on the bones and also the outcome of the planned activity.

Thousands of these oracle bones were stored in the king's archives. The first king whose name appears in the inscriptions is that of Wu Ding 武丁, who lived around 1200 BCE. Dong Zuobin 董作賓 (1895-1963) divided the oracle inscriptions into several historical phases, depending on language, the names of the diviners, and other criteria:

| Kings Pan Geng 盤庚 to Wu Ding 武丁 (c. 1280-1180) |

| Kings Zu Geng 祖庚 and Zu Jia 祖甲 (1179-1140) |

| Kings Lin Xin 廩辛 and Kang Ding 康丁 (1139-1130) |

| Kings Wu Yi 武乙 and Wen Ding 文丁 (1129-1084) |

| Kings Di Yi 帝乙 and Di Xin 帝辛 (1184-1027) |

The excavation of the oracle bones proved that the stories about the Shang dynasty, as reported in ancient histories like the Shiji 史記 were not simply pure mythology but historical facts. The oracle bone inscriptions of Yin make evident that at least the Shang rulers, as listed in the later historiographies, really existed.

During the later part of the Shang dynasty, the king took over the role of the diviner, which had been shared by different diviners during the early Shang. Only the last few rulers of Yin did not personally make divinations. Until then, each diviner had a special topic or subject he was a professional in, e.g., one diviner for warfare, one for ancestral rites, one for household affairs, and so on. It was usual to make divinations for a ten-day week (xun 旬, see Chinese calendar) and during certain special days of that week.

After many decades of studying oracle bone inscriptions, approximately 1,200 characters have been identified, of which about half can be translated. The meanings of the others remain unknown. In dictionaries and reference books, oracle bone characters are usually organised according to a radical system.

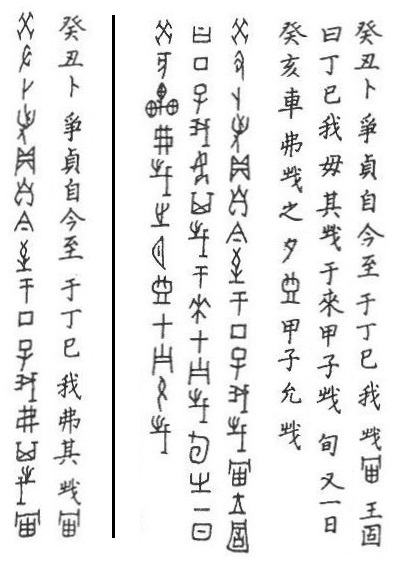

Before the divination process, the bone (scapula) or tortoise shell (plastron) was cleaned and polished. Oval and round hollows (aoxue 凹穴; the number is depending on the thickness of the material) were chiselled or drilled in parallel rows on the back side of the bone. The diviner placed a very hot round item (more details are unknown) in the hollows. The heat produced cracks (bu 卜) on the polished front side of the bone. The first task of the diviner after the divination had taken place was to incise the sequential number of the burning spots (crack numbers, xushu 序數) of the whole divination set (chengtao 成套), in tortoise shells typically alternating between two parallel rows on the surface, in other, lengthy bones from top to bottom. The whole inscription of a divination (buci 卜辭, zhaoyu 兆語) consists (ideally) of several parts:

| Preface (xuci 序辭 or 敘辭), indicating the date and the diviner (like: "crack-making on day XY, NN divined") |

| Charge (mingci 命辭), indicating the topic or question of the divination, often in positive and negative pairs (duizhen 對貞, like "will there be rain?/will there not perhaps be rain?") |

| Prognostication (zhanci 占辭), an interpretation of the resulting cracks, often made by the king |

| Verification (yanci 驗辭), record of actual events verifying the divination |

The Chinese terms are not original but were invented by modern Chinese scholars studying the Shang oracle inscriptions.

|

[negative, left side] Crack-making on guichou day, Zheng 爭 divined: "From today to dingsi day, we will not perhaps harm the Zhou 冑." |

| [positive, right side][Preface] Crack-making on guichou day, Zheng divined: [Charge] "From today to dingsi day, we will harm the Zhou." [Prognostication] The king, reading the cracks, said: "[Down to] dingsi day, we should not perhaps harm [them]; on the coming jiazi day we will harm [them]." [Verification] On the eleventh day, guihai day, [our] chariots did not harm [them]; in the tou period ['midnight'] between the evening and jiazi day, [we] really harmed [them]. | |

Central text of the obverse side of the plastron above, in two literally mirrored (to be seen in the first three characters) versions, one positive, and one negative. Sources: [Text and transcription] Yao Xiaosui, Xiao Ding (1988), Vol. 1, No. 6834. [Rubbing] See figure above. [Translation] Keightley (1978), [41]. |

|

Typically, the scribes would first incise the vertical strokes of the characters, followed by the horizontal strokes. The characters in the text, sometimes along with cracks caused by heat, could be filled with cinnabar or ash to enhance readability. Occasionally, the text was not incised but written with a brush. The position of the writing depended on the shape of the crack and which side of the plastron the crack appeared on. Remarks referring to a crack running to the left were inscribed on the right, and vice versa. These conditions also influenced whether the text columns were written from right to left, as is customary in traditional Chinese texts and still practised in Taiwan and Hong Kong, or from left to right. It was quite common to prepare two oracles for the same charge—one on the left side and one on the right side of the plastron, with one bearing a negative charge or question, and the other a positive charge.

The first scholarly study on the oracle bone inscriptions was Sun Yirang's 孫詒讓 (1848–1908) Qiewen juli 契文舉例. It was followed by many further studies of which only the most important shall be mentioned here:

| 契文舉例 | Qiewen juli | 孫詒讓 Sun Yirang |

| 殷墟書契考釋 | Yinxu shuqi kaoshi | 羅振玉 Luo Zhenyu |

| 殷墟文字記 | Yinxu wenzi ji | 唐蘭 Tang Lan |

| 古文字學導論 | Guwen zixue daolun | 唐蘭 Tang Lan |

| 耐林廎甲骨說 | Nailinqing jiagu shuo | 楊樹達 Yang Shuda |

| 積微居甲骨說 | Jiweiju jiaguo shuo | 楊樹達 Yang Shuda |

| 卜辭通纂考釋 | Buci tongzuan kaoshi | 郭沫若 Guo Moruo |

| 殷契粹文考釋 | Yinqi cuiwen kaoshi | 郭沫若 Guo Moruo |

| 甲骨文字研究 | Jiagu wenzi yanjiu | 郭沫若 Guo Moruo |

| 甲骨文字釋林 | Jiagu wenzi shilin | 于省吾 Yu Shengwu |

| 殷卜辭中所見先公先王考 | Yin buci zhong suo jian xiangong xianwang kao | 王國維 Wang Guowei |

| 中國古代社會研究 | Zhongguo gudai shehui yanjiu | 郭沫若 Guo Moruo, 董作賓 Dong Zuobin, 胡厚宣 Hu Houxuan |

| 殷曆譜 | Yin lipu | 郭沫若 Guo Moruo, 董作賓 Dong Zuobin, 胡厚宣 Hu Houxuan |

| 甲骨學商史論叢 | Jiaguxue Shangshi luncong | 郭沫若 Guo Moruo, 董作賓 Dong Zuobin, 胡厚宣 Hu Houxuan |

| 殷墟卜辭綜述 | Yinxu buci zongshu | 陳夢家 Chen Mengjia |