Genealogies (pudie 譜牒) served as records of family history in ancient China. They were biographical genealogies kept with the purpose of underlining the social and political importance of a family. The science of family records is called puxue 譜學 "genealogy".

The earliest genealogy in China is the book Shiben 世本 that has survived in several different versions. It describes the genealogies of dynasties and rulers of the regional states from the mythological past to the end of the Spring and Autumn period.

During the Three Empires 三國 (220-280) and Southern and Northern Dynasties period 南北朝 (300~600), it became essential for the eminent families (menfa 門閥, shizu 士族) to demonstrate their importance for law and order in the local areas of China, and to clarify their quality for producing candidates for high government offices. Genealogies became a vital means of accessing power. The central government actively consulted such genealogies in search of adequate candidates. Eminent families were furthermore exempted from tax-paying and labour corvée. Officials of the local government, therefore, regularly reviewed the genealogies to determine who was tax-liable and who was not, in order to prevent tax evasion. Eminent families intermarried with each other and therefore consulted the genealogies to find ideal matches for their sons and daughters.

In respect to ancestor veneration, genealogies were also vital to display the names of ancestors, whose personal names (hui 諱) could then be avoided to pay due respect to them.

During the Taiyuan reign-period 太元 (376-396) of the Eastern Jin era 東晉 (317-420), Jia Bi 賈弼 was the first to carry out an empire-wide collection of genealogies in order to record the most eminent families throughout the realm. His records were arranged geographically along the 18 provinces (zhou 州). At that time, the Jin dynasty 晉 (265-420) only ruled over nine provinces, the others being temporary "refugee provinces" (qiaozhou 僑州) founded by refugee families from the north. His staff compiled an enormous register with a length of 712 juan. This register was actualized during the Southern Qi period 南齊 (479-502) by Wang Sengru 王僧孺 (465-522), who supervised the compilation of the 710-juan-long Shiba zhou pu 十八州譜. The version from the Liang period 梁 (502-557) was 690 juan long.

Except for such general, empire-wide genealogies, there were also locally limited genealogies, like the Jiangzhou zhuxing pu 江州諸姓譜, Yuanzhou zhuxing pu 袁州諸姓譜, or the Yangzhou puchao 揚州譜抄. Other genealogies were restricted to one family cluster or "clan", like the Xieshi pu 謝氏譜 or the Yangshi xuemai pu 楊氏血脈譜. Understandably, eminent families preferred intermarrying with others of an equal standing. Some books have expressed these long-standing relationships between two or more families, like the book Qi Yongyuan zhong biaobu 齊永元中表簿.

|

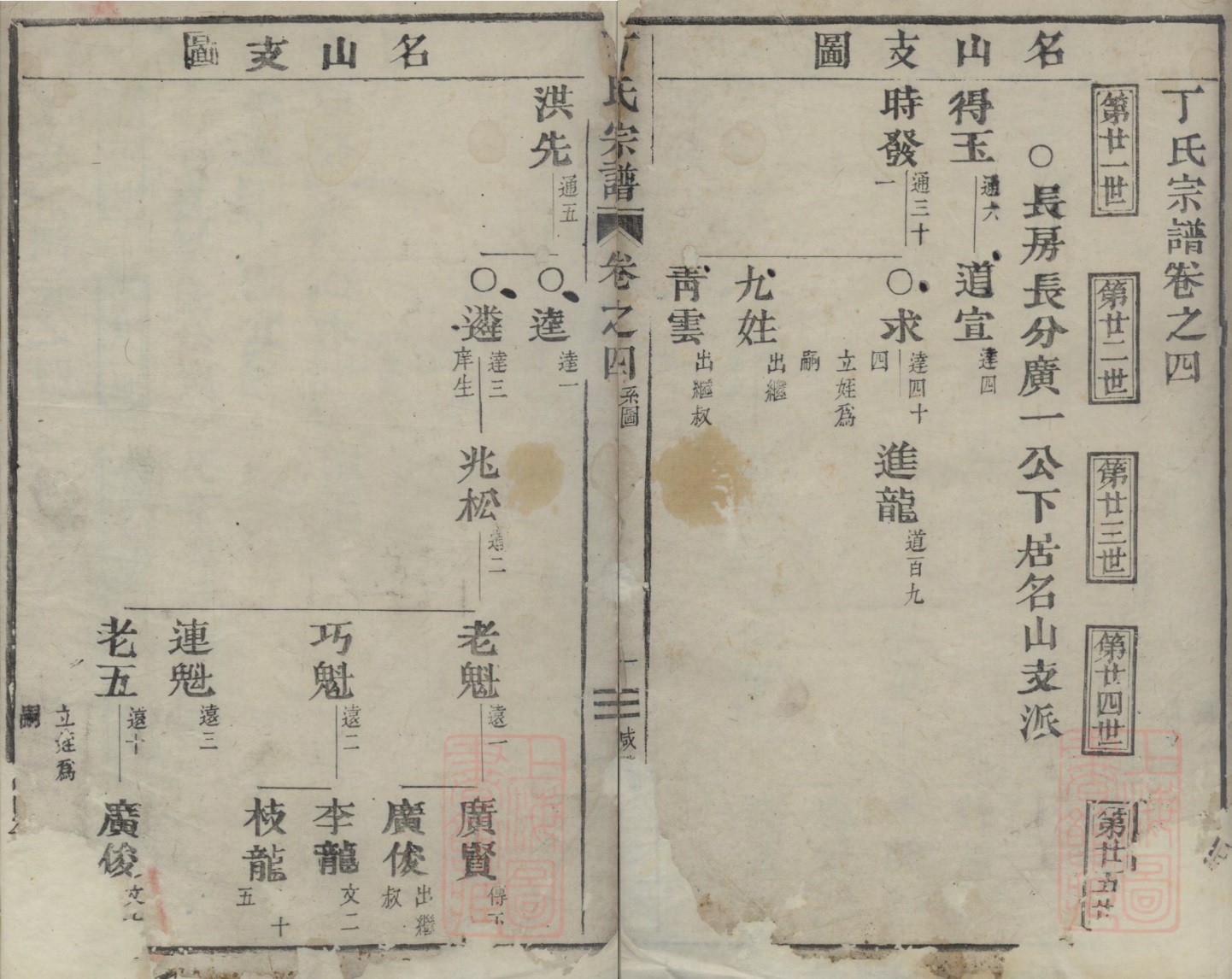

Family tree from Dingshi zongpu 丁氏宗譜 from 1857, showing the Mingshan branch 名山支派 of the Ding family. Copy owned by Shanghai Library (Shanghai Tushuguan 上海圖書館). |

From surviving data it can be reckoned that during the Southern and Northern Dynasties period, there must have been about 23 empire-wide genealogies (zongpu 總譜), 62 genealogies of individual families (jiapu 家譜, jiazhuan 家傳, jiadie 家牒, shizhuan 世傳), 15 genealogies of dynastic houses (huangshipu 皇室譜), and 13 geographical genealogies. Only a tiny part of these was written in northern China.

Under the Liang dynasty, an office for genealogies (puju 譜局) was founded. The descendants of Jia Bi continued his work and were the most critical compilers of genealogies, like Jia Feizhi 賈匪之, Jia Yuan 賈淵 (439-501, during the Tang period 唐 (618-907) called Jia Xijing 賈希鏡, in order to avoid the personal name of Emperor Gaozu 唐高祖, r. 618-626, Li Yuan 李淵), Jia Zhi 賈執, and Jia Guan 賈冠. Other genealogists were Xiao Jian 蕭儉, the Prince of Langya 琅琊, and Xiao Sengru 蕭僧孺, the Prince of Donghai 東海. The historiographer Liu Zhiji 劉知幾 (661-721)called them the "Two Princes of North of the Yangtze" (Jiang zuo liang wang 江左兩王).

|

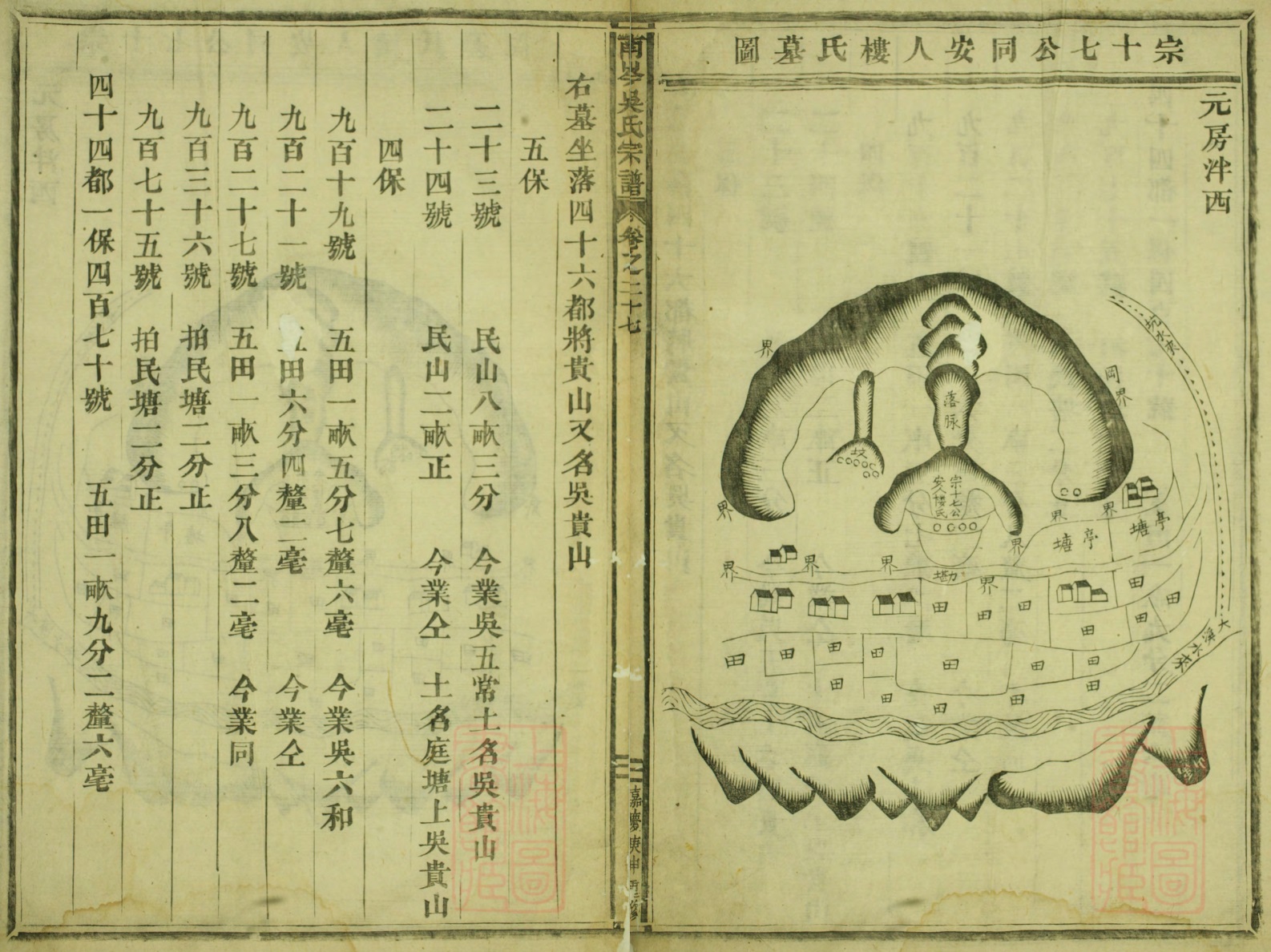

Image of a burial site in Nancen Wushi zongpu 南岑吴氏宗譜 from 1800, edited by Master/family Wu from Dongyang 東陽吳氏 showing a grave area surrounded by fields and mountains. While the mountains were protecting the graves according to principles of geomancy, the fields were used to finance sacrifices. Copy owned by Shanghai Library (Shanghai Tushuguan 上海圖書館). |

Due to the heavy impact of warfare in northern China, many genealogies were lost. Wei Shou 魏收 (507-572) from the Northern Qi period 北齊 (550-577) attempted to collect surviving copies for the compilation of the ordinary and collective biographies (liezhuan 列傳) of the history of the Northern Wei dynasty 北魏 (386-534), known as the Weishu 魏書. The imperial bibliography Jingji zhi 經籍志 in the official dynastic history Suishu 隋書, written during the early Tang period, includes only a minimal amount of genealogies from the north.

It is known that there was a tabloid register of the northern families, known as Fangsige 方司格 (also written 方思格). This register was quite simple and served to provide an overview of the general situation of the eminent families. It was not, like in the south, a detailed biographic report of all important family members. Unfortunately, only rare fragments of the genealogies from the Southern and Northern Dynasties periods survive. Some information is included in the table Xiangzai shixi biao 宰相世系表, which is part of the dynastic history Xintangshu 新唐書 (ch. 71-75), and in Wang Zao's 汪藻 (1079-1154) Shishuo renming pu 世說人名譜. Both sources date from the Song period 宋 (960-1279), which is much later than the originals.

Genealogies were still important during the first half of the Tang period. During that time, large, empire-wide genealogies were compiled, such as the Yuanhe xingzuan 元和姓纂, Xingshilu 姓氏錄, or Zhenguan shizu zhi 貞觀氏族志. From the second half of the Tang period onward, military power became more important than genealogy, and under the Song, the examination system for official recruitment replaced the former system based on recommendation and family status.

For private purposes, genealogies continued to be compiled. From the Song period on, the term zongpu 宗譜 became common for private genealogies, as well as designations like shipu 世譜, shidie 世牒, jiacheng 家乘, jiaji 家記, jiazhi 家志, pulu 譜錄, pulüe 譜略, etc. In the course of generations, each genealogy had to be revised. The individual version were, accordingly, given a prefix like chupu 初譜 "original records", laopu 老譜 "ancient records", xinpu 新譜 "new records", jinpu 近譜 "recent records", or xupu 續譜 "continued records".

|

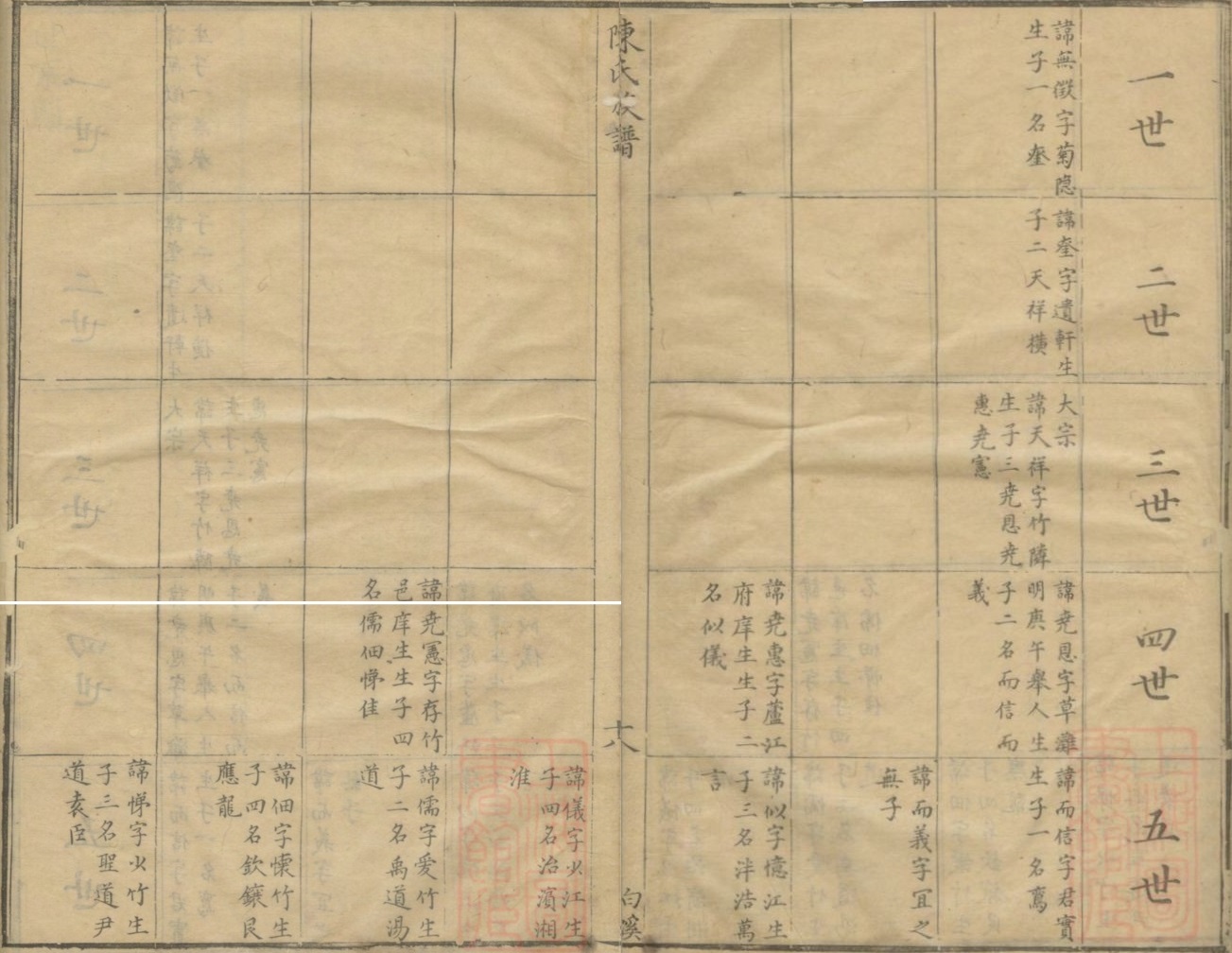

Family tree in grid-form in Baixi Chenshi jiasheng 白溪陈氏家乘, Qing period, edited by Chen Xingcan 陳星燦 from Wuxian 吳縣 (Suzhou 蘇州). Copy owned by Shanghai Library (Shanghai Tushuguan 上海圖書館). |

Large family clusters ("clans") often had their genealogies written in compound versions, known as tongpu 通譜, tongpu 統譜, quanpu 全譜 or huipu 會譜. In contrast, those of a particular family branch were called zhipu 支譜, fenpu 分譜, or fangpu 房譜. Family registers of an imperial dynasty - the imperial genealogy - were called yudie 玉牒 "jade registers" or xingyuan jiqing 星源集慶 "unified auspices of those originating from the stars".

Family registers or family trees (puxi 譜系) were often drawn up in a tabloid shape, which was invented by Su Xun 蘇洵 (1009-1066). Additionally, information was given about imperial grants (enrong 恩榮), shrines (ciyu 祠宇), tombs, biographies, and writings of family members. The family trees include information about the origin of the family, its dwelling place, and all male members, as well as some female members. The section of "imperial grants" mainly includes a list of graduates of provincial and metropolitan examinations as well as imperial edicts directly issued to the family, mainly including the award of titles like zhongyi 忠義 "of loyal conduct" or lienü 烈女 "eminent females", or the bestowal of "academic titles" (e.g., provincial or metropolitan graduate) by grace.

The section about the shrines includes a description of their location, as well as instructions from family ancestors to the family (zugui 族規, jiaxun 家訓) and the family's donation to the public community. The tombs section includes the inscriptions incised into the stone slabs. Some genealogies include tables and portraits of ancestors, shrines, estates and tombs.

The number of genealogies is immense, and not all of them have been published. The most extensive collection of Chinese genealogies is housed at the Genealogical Society of Utah. The majority of the more than 10,000 genealogies were collected in Taiwan during the 1970s and 1980s. More than half of these date from the Qing period 清 (1644-1911), several thousand from the Republican period (1912-1949), and less than 100 from the Ming era 明 (1368-1644) and earlier. In Southern China it was apparently far more common to compile genealogies than in the north. Among the southern provinces, Jiangsu and Zhejiang are the most productive areas.