Muzhiming 墓志銘, also written 墓誌銘, refers to a special type of tomb inscription inscribed on a stone placed in front of the tomb chamber. The terms zangzhi 葬志, fenji 墳記, maiming 埋銘, guoming 槨銘, kuangzhi 壙志, and kuangming 壙銘 all denote the same, but they are used less frequently. Inscriptions created for a re-burial at a different tomb site are called xuzhi 續志, houzhi 後志, guifuzhi 歸附志 (if the new site was within the home district of the dead person), or qianfuzhi 遷附志. The term quancuozhi 權厝志 was used for inscriptions made public during a wake if it was organised at the burial site.

Scholars like Xu Shizeng 徐師曾 (1517-1571), in his Wenti mingbian xushuo 文體明辨序說, distinguish between muzhi 墓志 and muming 墓銘, the former written in prose and the latter as lyrical texts. Most, but not all, inscriptions combine these two styles, and Xu demonstrates that the terms zhi and ming were not used consistently; they were often mistakenly interchanged. Han Yu's 韓愈 (768-824) Dianzhong shaojian Ma jun muzhiming 殿中少監馬君墓志銘 is primarily a prose text, while his inscription Lu Hun muzhiming 盧渾墓志銘 is solely a poem, even though both titles include the words zhi and ming. Han Yu's Liu Zihou muzhiming 柳子厚墓志銘 is a eulogy summarising in prose style. Some inscriptions feature an introduction (xu 序).

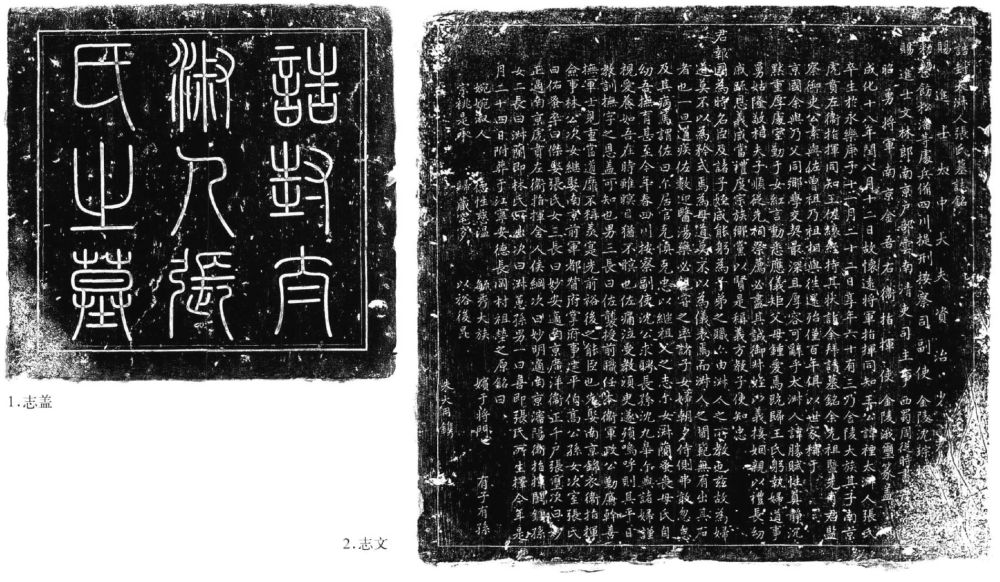

The stones on which muzhiming texts were carved were usually square and relatively flat. Tombstones consisted of two parts: a base (di 底) stone that held the prose and laudatory poem, and a cover (gai 蓋) that displayed a kind of title, such as the name and official laurels of the tomb owner. In earlier times, muzhi inscriptions were carved in ceramics (zhuanming 磚銘) or on wooden boards (then called fenban wen 墳版文 or muban wen 墓版文). Zhang (1992) suggests that muban wen were neither muzhiming nor mubei wen 墓碑文 (large stele inscriptions), but a term used for various tomb inscriptions, including beiji 碑記 (on the back of steles, beiyin wen 碑陰文), muzhiming, and mubei wen. The word ban 版 does not mean board nor that they were not yet carved into stone.

|

Rubbing of the inscription of a two-part buried tomb stone. The cover with the title of the inscription, written in seal script, is seen on the left (it says Gao feng taishuren Zhang shi zhi mu 誥封太淑人張氏之墓 "Tomb of Ms Zhang, who was granted the title of Grand Lady of Virtue"), while the inscription is presented on the right hand. The inscription consists of a long prose text (zhi, and a short final eulogy in poetry form (ming). From He 2013. |

Because the text was written in embellished and beautiful language and might have been "composed" by famous writers (yu muwen 諛墓文), muzhiming inscriptions were counted as a literary genre of its own, and were collected as examples of quality literature. Quite famous are Yu Xin's 庾信 (513-581) Zhou Dajiang Huaide gong Wu Mingche muzhiming 周大將軍懷德公, Han Yu's Liu Zihou muzhiming, Ouyang Xiu's 歐陽修 (1007-1072) Yi Shilu muzhiming 尹師魯墓志銘, Gui Youguang's 歸有光 (1507-1571) Shen Zhenfu muzhiming 沈貞甫墓志銘, Fang Bao's 方苞 (1668-1749) Chen Yuxu muzhiming 陳馭虛墓志銘 or Peng Ji's 彭績 (1742-1785) Wang qi Gong shi kuangming 亡妻龔氏壙銘. There are also separate collections of tomb inscriptions like Wang Xing's 王行 Muming juli 墓銘舉例 from the Ming period 明 (1368-1644).

While large, detailed, and representative tomb inscriptions like mubei, mujie 墓碣, or mubiao 墓表 were carved on stone steles or tablets erected either in front of, behind, or beside a grave or on the side of a soul path, muzhiming were inscribed on stones buried close to the tomb pit or just before the burial chamber. This was done to prevent deliberate destruction and also to ensure that, if the stele was lost, later generations would know the owner of the tomb. Muzhiming stones can therefore be regarded as a kind of grave furniture.

Moreover, muzhiming stones were placed before the interment, while mubei were erected later, also because their inauguration required official approval. Muzhi-type tomb inscriptions were sometimes a gift from a sovereign to a highly esteemed state official. All types of tomb inscriptions aimed to present the name and origin of a tomb owner and to praise their achievements in political and social fields. The lyrical part, ming, was usually a concluding praise of the moral virtues of the deceased.

The custom of buried grave stones emerged during the Southern Dynasties period 南朝 (420-589), but the first mentioned example was a tomb stone of Du Zixia 杜子夏 (Du Qin 杜欽) during the very late Former Han period 前漢 (206 BCE-8 CE).