The so-called yulin tuce 魚鱗圖冊 "fish scale map registers", short yulince 魚鱗冊, were field catasters for the purpose of taxation. Because the maps were drawn quite crudely and the particular parcels of land therefore had the round shape of fish scales the registers were given this strange name. The first idea on fish scale registers dates from the prefectures of Wuzhou 婺州 and Zhangzhou 漳州, Fujian. They were planned during the Southern Song period 南宋 (1127-1279), but probably never carried out in practice. The method became most widespread during the Ming period 明 (1368-1644). The founder of the Ming dynasty dispatched a large group of tax inspectors under Zhou Zhu 周鑄 to the province of Zhejiang to survey the land allotments of the rich gentry of that region. This objective was to forestall tax evasion. The result of the survey was recorded as a clearance book (qingce 清冊) which served for taxation.

|

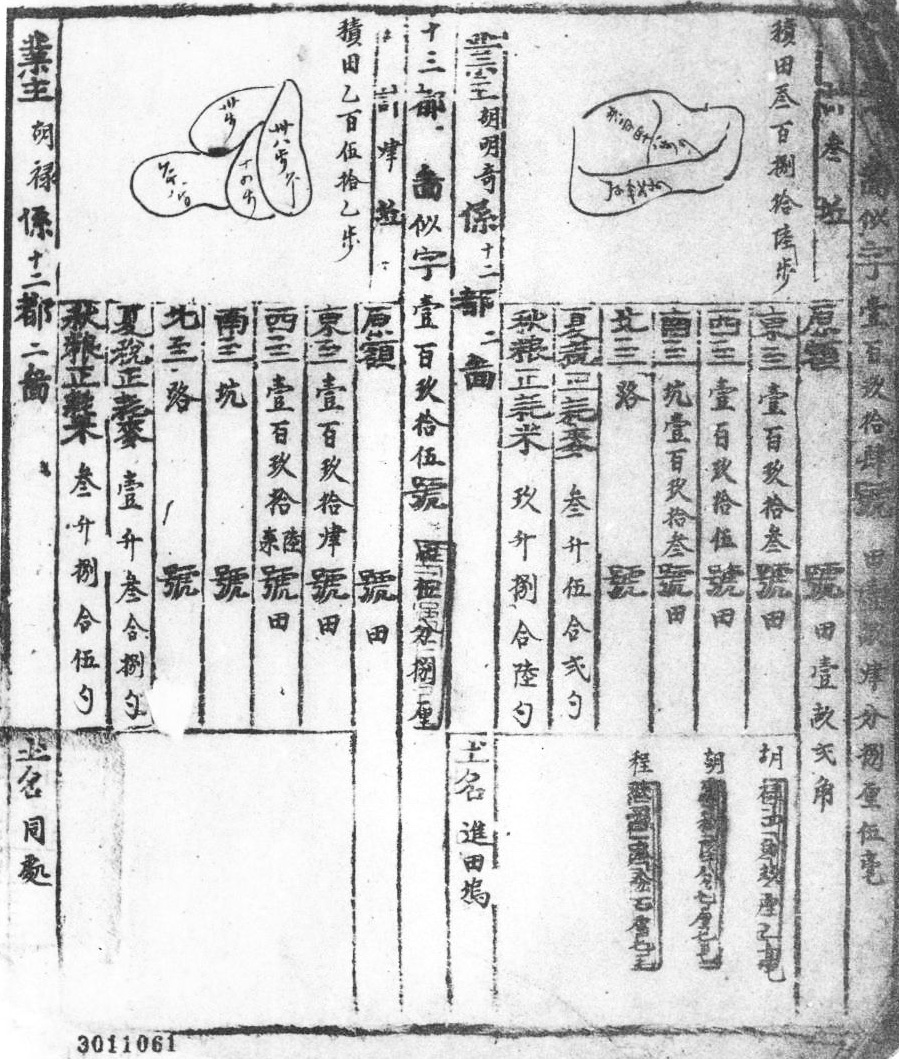

Ming Jixi xian shisan du si zihao jingli baobu 明績溪縣十三都似字號經理保簿. Source: Zhongguo shehui kexue yuan Lishi yanjiu suo (1993), Vol. 18, p. 79. |

Basis for the registers was the tax revenue quota of each district (xian 縣). The arable surface of the district was thereupon divided into plots (qu 區), each plot corresponding to approximately the same amount of grain to be yielded (sui liang ding qu 隨糧定區 "determining the plots according to the amount of grain"), namely 10,000 shi 石 (a weight measure, see weights and measures). The fields within these plots were surveyed in cooperation with the community heads (lizhang 里長) and tithing chief (jiashou 甲首, see lijia 里甲, rural self-administration). The guiding person was the tax captain (liangzhang 糧長). Each field was registered according to its size and the quality of the soil in order to assess an output and, accordingly, a tax quota to be delivered. The register included four positions including the size, shape, and fertility of the land, and the name of the owner.

The registers were then compiled for each district, and assembled for the whole prefecture. The prefecture produced four copies, one of which stayed in the district, one in the prefecture, one was sent to the provincial treasury (buzhengshi si 布政使司), and one to the Ministry of Revenue (hubu 戶部). Generally the fish scale map registers provided a relatively reliable source for taxation and helped amending many shortcomings. It was more soil registered than ever before, and this helped the government obtaining higher tax revenues. After first positive experiences an empire-wide census was organised in 1391, and the whole empire was surveyed according to this method, under the supervision of Wu Chun 武淳. The registered arable land increased from 3,667,700 qing 頃 (a measure of area) in 1381 to 3,874,700 qing and the tax revenue increased in the same time from 26 million dan 石 (a measure of capacity) to 32 million dan of grain. The last fish-scale registers were compiled in 1866.