The historiographical genre of jinshenlu 縉紳錄 "records of the gentry" (also found as 搢紳錄, because state officials had a tablet of merit [hu 笏] "stuck in their girdle" jin shen 搢紳) or roster of government personnel focuses on the careers of members of the gentry, a significant part of whom held official positions. The documents record each step on the ladder of success (zhizhang 職掌 "offices held"), beginning with graduation in the state examinations (chushen 出身 "excelling"), and link individual persons to the register of a family or clan (jiguan 籍貫 "home register"). They provide essential information on the careers of particular individuals, the success of their families or family clusters ("clans"), and the occupation of state offices by middle and lower-ranking officials.

The precursors of this genre can be found in Southern Song-period 南宋 (1127-1279) records like the banchaolu 班朝錄, but it gained importance during the Ming period 南宋 (1127-1279), with examples as Xinkan zhen-kai dazi quanhao jinshen bianlan 新刊真楷大字全號縉紳便覽, Xinkan Nan-bei Zhili shisan sheng fu zhou xian zheng-zuo shouling quanhao huanlin beilan 新刊南北直隸十三省府州縣正佐首領全號宦林備覽 (both printed by Ye Co., Iron Workers Lane 鐵匠胡同葉鋪 in Beijing, 1584) or Xinkan xiangzhu jinshen bianlan 新刊詳注縉紳便覽 (Hong's Printing Shop 洪氏剞刷齋, c. 1640). From the titles, it can be seen ("new", "in large standard characters", "complete", "detailed") that such collections were private publications, which necessitated advertisements and lengthy, descriptive titles.

The number of publications increased during the Qing period 清 (1644-1911). The most important types are (Man-Han) Juezhi quanlan (滿漢)爵秩全覽, (Man-Han) Juezhi xinben (滿漢)爵秩新本, Juezhi quanhan 爵秩全函, Neiwufu juezhi quanlan 內務府爵秩全覽 (only the Imperial Household), Da-Qing jinshen quanshu 大清縉紳全書, Da-Qing zhongshu beilan 大清中樞備覽 (military officials only), Da-Qing shiji quanbian 大清仕籍全編, Jinshen xinshu 縉紳新書, Da-Qing rixin zhiguan lu 大清日新職官錄 or Da-Qing zuixin baiguan lu 大清最新百官錄. Tsinghua University 清華大學 owns quite a few collections and had them published in the series Qingdai jinshen lu jicheng 清代縉紳錄集成 (Guojia Qingshi bianzuan weiyuanhui 國家清史編纂委員會, ed., Beijing: Daxiang chubanshe, 2008), including 209 books.

|

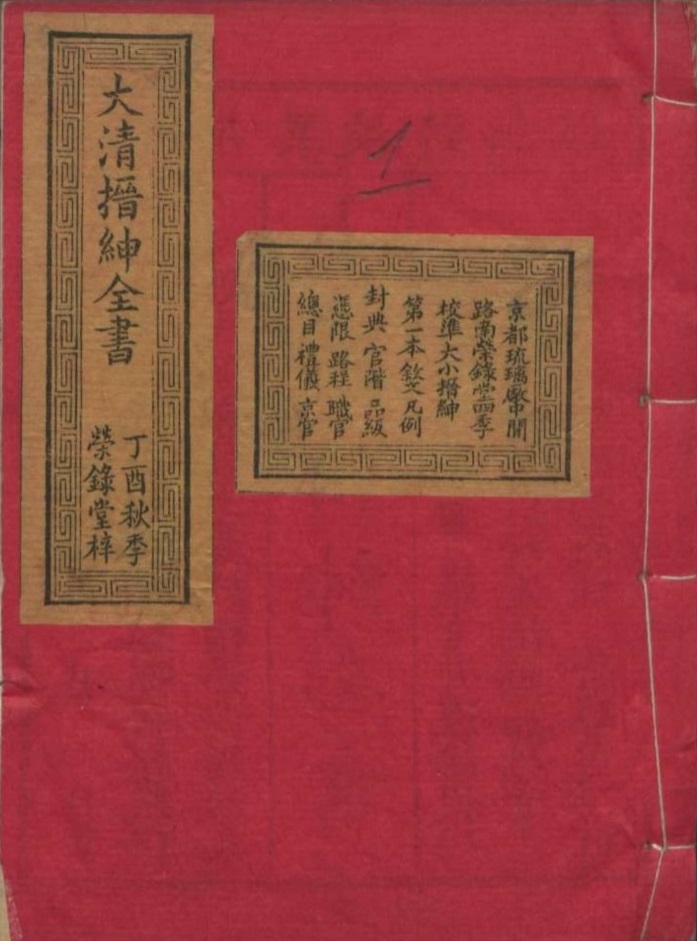

Da-Qing jinshen quanshu 大清搢紳全書 from autumn 1897 ([光緒]丁酉秋), published by the Ronglu Studio 榮録堂. The sticker provides the address of the publisher and a brief table of contents. Source: Staatsbibliothek Berlin. |

Among them are official publications (guanke 官刻) and private publications (fangke 坊刻). While the print quality of the official publications is generally good, that of the private ones is quite diverse. Similar lists of government officials were called Timing beilu 題名碑錄, Guanxuanlu 館選錄, Yushi timing 御史題名, Wen-wu jinshen 文武縉紳, Timinglu 題名錄, Tongguanlu 同官錄 or Chilu 齒錄. The earliest surviving roster of the Qing period dates back to 1775 and is housed by the Library of Nankai University 南開大學圖書館. Most publications date from the very late Qing period, for instance, the most widespread version of the Da-Qing jinshen quanshu from 1903.

Persons serving in higher offices of the central or provincial administration are documented well in quasi-official biographies found in the official dynastic history Qingshigao 清史稿 or collections like Qingshi liezhuan 清史列傳, Guochao qixian leizheng 國朝耆獻類徵, or Qingguoshi 清國史. Yet the personal history of officials in lower positions is not easily traceable. Apart from local gazetteers, the gentry records are an ideal source for finding out more about the lower and middle levels of the Qing bureaucracy. The careers were initially recorded in the archive of the Ministry of Personnel (libu 吏部) and, in the case of military personnel, the Ministry of War (bingbu 兵部). The Ministry of Personnel had offices organising the staffing of the officialdom, namely the Bureau of Appointments (wenxuan qinglisi 文選清吏司), the Bureau of Evaluations (kaogong qinglisi 考功清吏司), the Bureau of Honours (yanfeng qinglisi 驗封清吏司), and the Bureau of Records (jixun qinglisi 稽勳清吏司), where the educational and the bureaucratic careers were minutely recorded. Revisions were based on the monthly reports (dichao 邸抄) each institution had to submit to the central government. In the provinces, this work was done by a provincial courier (titang 提塘).

In 1905, the Ministry even founded a *Roaster Office (jinshenchu 縉紳處) which handled the monthly reports (jincheng yuezhe 進呈月折), the handing over of "circulation booklets" reporting on tax collection (xunhuanbu 循環簿), the quarterly revision of the records, as well as other issues concerning the officialdom (jingcheng 經承). The documents were printed and thus made official historiography. In summer 1911, the Grand Secretariat (neige 内閣) transferred the organisation of the prints to the Printing and Press Office (yinzhuju 印鑄局).

The frequency of publication was determined by the updating of the registers of office holders which made the private gentry registers almost a type of "quarterly" gazetteer. The quarterly compilations, supervised by the Bureau of Appointments, were submitted to the Emperor for information. The number of private prints is considerable and was produced by between 60 and 70 printing shops or editors (Kan 2017: 107). The most famous among them were the Ronglu Tang 榮録堂, the Ronglu Tang 榮祿堂 and the Rongjin Zhai 榮晉齋 editors. Some printing shops of the Liulichang area 琉璃廠 of Beijing, like the Tongsheng Ge 同升閣, even specialised in gentry records – the so-called jinshenpu 縉紳鋪 "roster shops". It was common for freshly appointed officials to give them as presents to friends and family members to demonstrate their success in state examinations and their career, as it was visible in the respective name registers (mingce 名冊). Most private publications were wrapped in red sleeves and were therefore known as hongmian 紅面. The cover usually also bore the designation and address of the publisher, as well as a brief table of contents. The cover was often made of coarse paper, and the edition was printed in a small "pocket" format (xiaoben 小本, jinxiangben 巾箱本). However, there were also large private editions (daben 大本) that imitated the official versions.

|

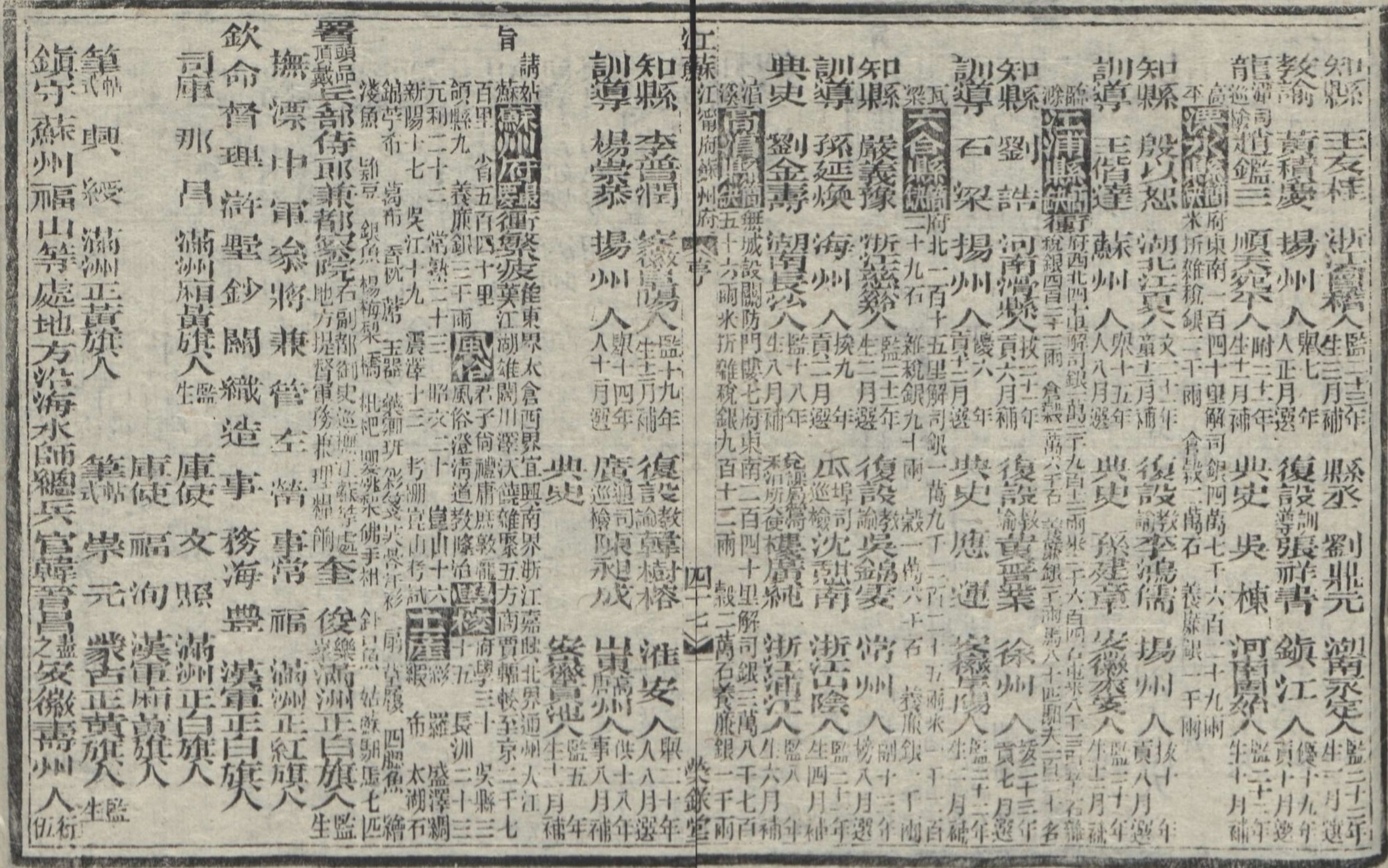

Leaf showing the holders of offices in the administration of several districts of Jiangsu and the prefectural administration of Suzhou 蘇州. The districts of Lishui 溧水, Jiangpu 江浦, Luhe 六合 (sic), and Gaochun 高淳 were "easy lots" (jianque 簡缺), while the post of prefect of Suzhou was very important (zuiyao 最要) because it was demanding in three respects (chong fan pi 衝繁繁). The roster provides information on the customs (fengsu 風俗), schools (xuexiao 學校), and local products (tuchan 土產). The incumbent prefect was Kuijun 奎俊, courtesy name Lefeng 樂峯, from the Manchu Plain White Banner (Manzhou zhengbai qi 滿洲正白旗). He had achieved the grade of a university student (jiansheng 監生), had been Vice Minister of War (bingbu shilang 兵部侍郎) and (Right Vice) Censor (you fu duyushi 右副都御史), and was allowed to bear a first-class hat button (toupin dingdai 頭品頂戴). Source: Staatsbibliothek Berlin. |

The arrangement of jinshenlu texts followed a hierarchical sequence, with the Capital offices first, and the provinces thereafter. The detailed arrangement and content of private rosters were not standardised, but in many cases, the private versions provided more information than the official editions (Kan 2013: 56). In some cases, the private versions even contained 1,500 to 2,800 more records (Chen, et al. 2020: 439). The difference results in the recording of holders of temporary (shiyong 試用) or supernumerary positions (ewai 額外) or even information of "allotted" (fenfa 分發) persons who had purchased a title or an office (ibid.).

Commercial editions recorded ranks (pinji 品級) and titles (zhixian 職銜) of state offices and officials, their names and origin, date of graduation and appointment, and transfer to other functions, insignia like hat buttons, anti-corruption allowance (yanglianyin 養廉銀) and salary (xinfeng 薪俸). For local offices, the rosters also noted down the regional situation. They provided information on the adjacent territories (jiangyu 疆域, sometimes even with a map), the main roads, the structure of administration, finances and tax revenue, granary capacities, and local products and customs – in a way similar to the arrangement of local gazetteers.

Yet as a source on administrative matters and such of personnel, the gentry records also provide information whether a post in the local administration was an "easy" (jianque 簡缺), an "average" (zhongque 中缺), an "important" (yaoque 要缺), or a "very important" one (zuiyao 最要). This categorisation pointed to the importance of a local post with concrete functions (shique 實缺). Another categorisation took into consideration the difficulty of the administration in various fields, namely the situation of the roads and streets (chong 衝), the administrative requirements (fan 繁), the number of highwaymen and bandits in relation to the existing police forces (pi 疲) and the "difficulty" of the population (nan 難). The private editions added information on ranks and grades (guanjie pinji 官階品級) or time limits for taking over a post (furen pingxian 赴任憑限) as stipulated by the Libu zeli 吏部則例 regulations, routes with courier stations (yizhan lucheng 驛站路程) as described in the Da-Qing huidian 大清會典, lists of all state offices, ennoblements (fengdian 封典), persons on leave to tend ailing parents or to mourn for a dead partent (zhongyang dingyou 終養丁憂), (multiple) records for promotion in rank (jiaji jilu 加級紀錄), but also sub-official personnel (chaiwu 差務). The private rosters also provided information about ceremonial obligations when state officials met. All this information made rosters of state employees critical handbooks, or "compasses for the world of officialdom" (guanchang zhinan 官場指南, Kan 2013: 57).

Outsiders learnt more about the landscape of capital officials, making it easier to approach individual persons and establish connections, which helped manage affairs, gain access to vacations, and so on. Persons going to Beijing to curry favour with a person of high standing used to study the "five coloured books" (wu se shu 五色書), namely the gentry records with their red envelopes, the Beijing Gazette (Jingbao 京報) in yellow, the petition books (bingtie 禀帖) in black/dark, public announcements (zhihui 知會) in white, and the account books (zhangbu 賬簿) in blue/green. Many famous collectors, such as Wang Shizhen 王士禛 (1634-1711), Yang Fengbao 楊鳳苞 (1754-1816), Ji Yun 紀昀 (1724-1805), Ruan Yuan 阮元 (1764-1849) or Pan Zuyin 潘祖蔭 (1830-1890), purchased gentry records for their libraries.

The rosters also served to help newly appointed officials to obtain information about the local conditions and the names of future colleagues, superiors, and subordinated persons. They also helped to study the history of the own family and to admire or to boast about with their social achievements. The Taiping rebels 太平, founding an independent kingdom in southeast China, used the rosters to learn about local taxation. Foreign missionaries in Shanghai used them to make advertisements for the Christian creed. Even diplomats gained a deeper understanding of the personnel within the central government machine of Qing China through the jinshenlu rosters.

Private publishers obtained their information from the Bureau of Records (Chen 2019: 130). The rosters are, when compared to each other and with other sources, generally correct, with some exceptions like the provincial quota of provincial graduates (juren 舉人), as Zhang (2018) has shown. Private printed laid stress on correct statements and preferred leaving out information rather than making wrong statements. This method helped to give the name of their company a taste of quality. Because a new edition was due every three months, the private printers did not cut new plates, but instead replaced changing information with new types or inserted pages into older issues.

In the very late years of the Qing period, the rosters were gradually replaced by new types of handbooks, namely biographical dictionaries like the various Shangyoulu 尚友錄 or the Zhongguo renming da cidian 中國人名大辭典 (1921).

Recently, a Hong Kong-based project (China Government Employee Dataset—Qing, CGED-Q) began to digitise the rosters. The data help to answer many question about the government structure of late imperial China, to confirm that Manchu officials were systematically replaced by Chinese candidates (Hu 2018).