Taotie 饕餮 was a demoniac beast in Chinese mythology. The word is seen in early literature, but is mostly used for the theriomorphical designs of Shang 商 (17th-11th cent. BCE) and early Zhou period 周 (11th cent.-221 BCE) bronze vessels.

|

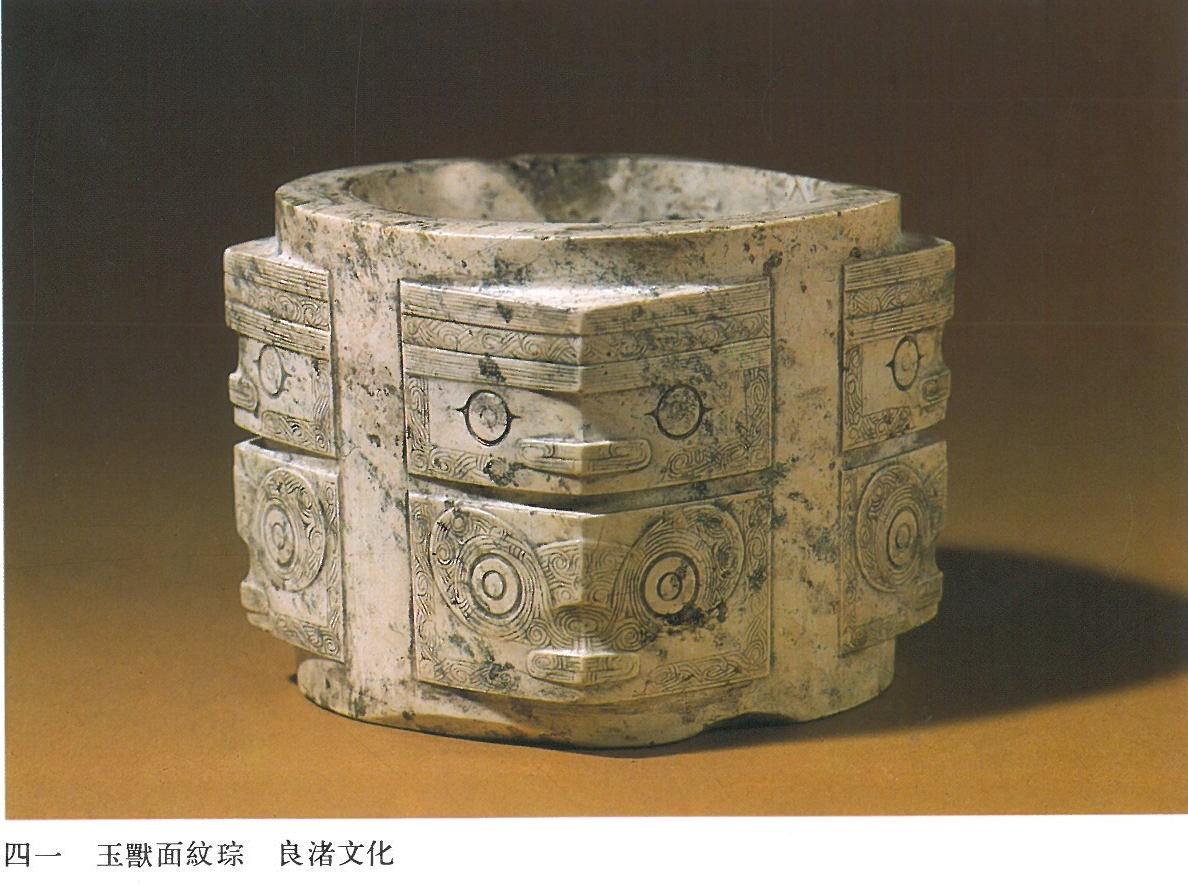

Jade cong 琮 with taotie pattern from the Liangzhu Culture 良渚文化. Source: Yang Boda 楊伯達 (1993), Zhongguo meishu quanji 中國美術全集, Gongyi meishu bian 工藝美術編, Vol. 9, Yuqi 玉器 (Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe), Plate 41. Click to enlarge (opens in new tablet). |

|

Tripod with simple taotie pattern, with eyes and body (bodies?), early Shang period. Li Xueqin 李學勤 (1993), Zhongguo meishu quanji 中國美術全集, Gongyi meishu bian 工藝美術編, Vol. 4, Qingtongqi 青銅器 (Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe), Plate 18. |

|

Square fangding vessel (Xiao chen fou fangding 小臣缶方鼎) with elaborate depiction of a taotie, with eyes, horns and fangs, late Shang period. Li Xueqin (1993), Zhongguo meishu quanji, Gongyi meishu bian, Vol. 4, Qingtongqi, Plate 121. |

|

Tripod with taotie pattern, earliest scholarly illustration in the Song period catalogue Xuanhe bogu tu 宣和博古圖, juan 1, fol. 42r (Siku quanshu edition). |

The term first occurs in the story collection Shenyijing 神異經 from the Han period 漢 (206 BCE-220 CE), where the taotie is described as an anthropomorphal animal, with hairs on the body, and [tusks? bristles?] of a pig on the head, and a "voracious appetite like that of a wolf", but not for human food. It was said to hoard precious items, and attacking only the weak and lone travellers (?).

The Shenyijing further explains that, according to the Classic Chunqiu 春秋 "Spring and Autumn Annals", the creature was originally an untalented son or descendant of a person called Jinyun 縉云氏. It was known as Tanlan 貪婪, Qiangduo 強奪 or Lingruo 凌弱, and "all persons in the land [of Jinyun] were like this". Indeed, the Zuozhuan Commentary 左傳 writes that "Jinyun [an officer in the time of the Yellow Emperor], had a descendant who was devoid of ability and virtue. He was greedy of eating and drinking, craving for money and property. Ever gratifying his lusts, and making a grand display, he was insatiable, rapacious in his exactions, and accumulating stores of wealth. He had not idea of calculating where he should stop, and made no exceptions in favour of the orphan and the widow, felt no compassion for the poor and exhausted. All the people under Heaven likened him to the three other wicked ones, and called him Glutton." (Transl. James Legge [1872], The Chinese Classics, V, The Ch'un Ts'ew with the Tso Chuen (London: Frowde), 283.)

The book Shanhaijing 山海經 describes an animal called Paohao 狍鴞, which was living in the mountains of Gouwu 鉤吾 and had the shape of a goat, but the face of a human, yet with tiger-like teeth and with claws. Guo Pu's 郭璞 (276-324) commentary from the Jin period 晉 (265-420) adds that the animal was greedy (tanlan 貪惏) and used to injure men, without killing or devouring them in the whole. This was, Guo says, the taotie mentioned in the Zuozhuan.

The animal is also mentioned in the book Lüshi chunqiu 呂氏春秋 (chapter Xianshi lan 先識覽), where the taotie is first related with the decoration of the bronze tripods of the Zhou period. The decoration showed just the heads, but not the bodies of the taotie. These beasts were keen at devouring humans, but were not able to swallow them, and therefore just harmed themselves, in a kind of retribution for evildoing (bao geng 報更). Some authors identify the taotie with Chi You 蚩尤, the mythological warrior enemy of the Yellow Emperor.

In the chapter on the southwestern barbarians (Xinanyi zhuan 西南夷傳) in the official dynastic history Houhanshu 後漢書, the taotie is described as a kind of "numinous" goat or sheep (lingyang 靈羊), parts of whose body (the horns?) could be used as medicine. Accordingly, the term dajiyang 大吉羊 "great auspicious goat" is often found in Han period iron implements or tools.

Patterns showing the face of a "voracious" beast appear as early as on the pottery of the Liangzhu Culture 良渚文化 of the Lower Yangtze area. In central China, zoomorph pictures on the pottery of the Erlitou Culture 二里頭文化 are the direct forerunners of the bronze vessel masks of the Shang period, but most of these early pictures mainly show fixing eyes, while the horns and patterns of the face only appear in the late Shang period. In the flourishing age of taotie patterns, these have some common features, namely symmetrical horns, no lower jaw, and a mask-like appearance, which might be a prove that they were used as masks worn by shamans during certain ceremonies. Various scholars tried to identify the taotie with some existing or mythological animals, like tigers, goats, serpents, or dragons. In some cases, the bodies of taotie are seen, making them appear like crocodiles, oxen, or stags.

The word taotie was first used for the decorative masks on bronze vessels by a handbook on the connoisseurship of antiques of the Song period 宋 (960-1279), Xuanhe bogu tu 宣和博古圖. From then on it was the common archaeological term for the masks. The Xuanhe bogu tu explains that the symbol of the taotie served as a warning against greed and lust (taotie yi jie qi tan 饕餮以戒其貪).