Dunhuang 敦煌, in older sources also written 燉煌, was the westernmost commandery (jun 郡) of the Han empire 漢 (206 BCE-220 CE). It was therefore a vital border post on the Silk Road and for the administration of the Chinese colonies in the Western Territories 西域.

In 121 BCE, the territory was seized from the control of the Xiongnu 匈奴 khan Hun-ya 渾邪, and the commandery of Jiuquan 酒泉 was created, only to be divided up ten years later into Jiuquan and the commandery of Dunhuang farther to the west. The commandery lived on under all different dynasties of China until the Tang period 唐 (618-907), when it was replaced by the prefecture (zhou 州) of Shazhou 沙州.

The name Shazhou had first been used by the Former Liang dynasty 前涼 (314-376), which chose Dunhuang as its seat of government. The Northern Wei dynasty 北魏 (386-534) reduced the status of Dunhuang to that of a defence command (zhen 鎮), and the short-lived Northern Zhou 北周 (557-581) administered the region as the district of Mingsha 鳴沙縣 "Singing Sand".

The rulers of the Sui dynasty 隋 (581-618) resumed the name of commandery of Dunhuang. During the early Tang period, it was first named prefecture of Guazhou 瓜州 (see note below) and was then renamed Xishazhou 西沙州 "Western Shazhou". From the mid-8th century on, the region came under the control of the kingdom of Tubo 吐蕃 (Tibet) and was later seized by the Uyghurs 回鶻. It was again named commandery of Dunhuang form 742 on. In 905, the military commissioner (jiedushi 節度使) Zhang Chengfeng 張承奉 proclaimed himself King of the Gold Mountain Country of Western Han (Xihan jinshan guo 西漢金山國), with Dunhuang as his capital.

During the Song period 宋 (960-1279), it was part of the Western Xia empire 西夏 (1038-1227). The Mongols again set up the prefecture of Shazhou in 1277 and made it the seat of an inspection circuit (lu 路). During the Yongle reign-period 永樂 (1403-1424) of the Ming dynasty 明 (1368-1644), Shazhou was a border garrison (wei 衛), but was never again given the status of a prefecture. In 1760, it was transformed into a district (xian 縣).

Dunhuang is very famous for the findings of Han- to Tang-period administrative documents that provide an excellent insight into the daily life in a border region. The oldest find of Han-period bamboo slips (Dunhuang Hanjian 敦煌漢簡) was made in 1907 by Aurel Stein (1862-1943) in the ruins of the relay watchtowers (fengsui 烽燧) of Dunhuang. It included 705 different documents. Six further finds were made in the following decades. There are 2,190 documents held by the British Museum, the Palace Museum in Taipei and the Provincial Museum of Gansu. They also include finds from the watchtowers in the commandery of Jiuquan 酒泉. Most of the Han-period documents are of bureaucratic character and report matters concerning the garrisons and the administrative units of the two commanderies. Yet there are also documents of medical, astronomical and mantic content, as well as fragments of China's oldest textbooks, the Cangjiepian 倉頡篇 and the Jijiupian 急就篇.

Other types of literature were discovered mainly in the Buddhist grottoes of Mogao 莫高窟. In 1900, Wang Yuanlu 王園籙 (1851-1931) discovered the first Buddhist writings in Cave 17. Other writings were found inside statues in 1944, and in 1965, a discovery was made in front of Cave 122. In total, more than 40,000 documents and writings were collected by discoverers of various nations. Besides the British Aurel Stein, there were the French Paul Pelliot (1878-1945), the Japanese Tachibana Zuichō 桔瑞超 (1890-1968), Yoshikawa Shōyichirō 吉川小一郎 (1885-1978), and the Russian Sergej F. Ol'denburg (1863-1934). As it was common during that time, they took the documents with them, a custom that led to the unfortunate situation that today documents are scattered in museums around the world, from London, Paris and Berlin to St. Petersburg and Kyōto. Yet there are at least some documents to be found in Shanghai, Beijing, Lanzhou, Tianjin and Taipei.

The most significant part of the Dunhuang documents is written in Chinese (the lesser part is written in Tibetan, Khotanese or Tokharian, Türkic, Uyghurian, Soghdian or in Sanskrit, the old language of India). The majority of documents was preserved in the shape of "scrolls" (juan 卷). From the 9th century on, the folded binding (zhezhuang 折裝) came into use. Some of the folded-binding documents were printed, whereas all other documents were hand-written previously. The earliest dateable document is the Shi song biqiu jie ben 十誦比丘戒本 from 405, while the youngest dates from 1002 and records a donation of a Western Xia 西夏 (1038-1227) prince to the local monastery.

Ninety-five per cent of the documents found in Dunhuang are of Buddhist content and include sutras, vinayas (monastic rules), explanations, commentaries, praises, dhāraṇīs 陀羅尼 (magic meditation texts), prayers, confessions, sacrificial texts, biographies of monks and library catalogues. Important sutras like the Jingangjing 金剛經 "Diamond Sutra" and Lianhuajing 蓮花經 "Lotus Sutra" were often copied. The Dunhuang findings also include Buddhist texts that were lost in the later canons, like those of the "Three Stages School" (sanjiejiao 三階教) and such reflecting the religious situation in Tibet, like the Lengjia shizi ji 楞伽師資記 and Wang Xi's 王錫 Dunwu dasheng zhengli jue 頓悟大乘正理訣.

Apart from Buddhist writings, some Daoist scriptures were also found in Dunhuang, like the Xiang'er 想爾 commentary on the Laozi daodejing 老子道德經, and the apocryphal writing Laozi huahu jing 老子化胡經. A few Manichean and Nestorian writings were also discovered, showing that both religions once attracted believers in the western regions of China.

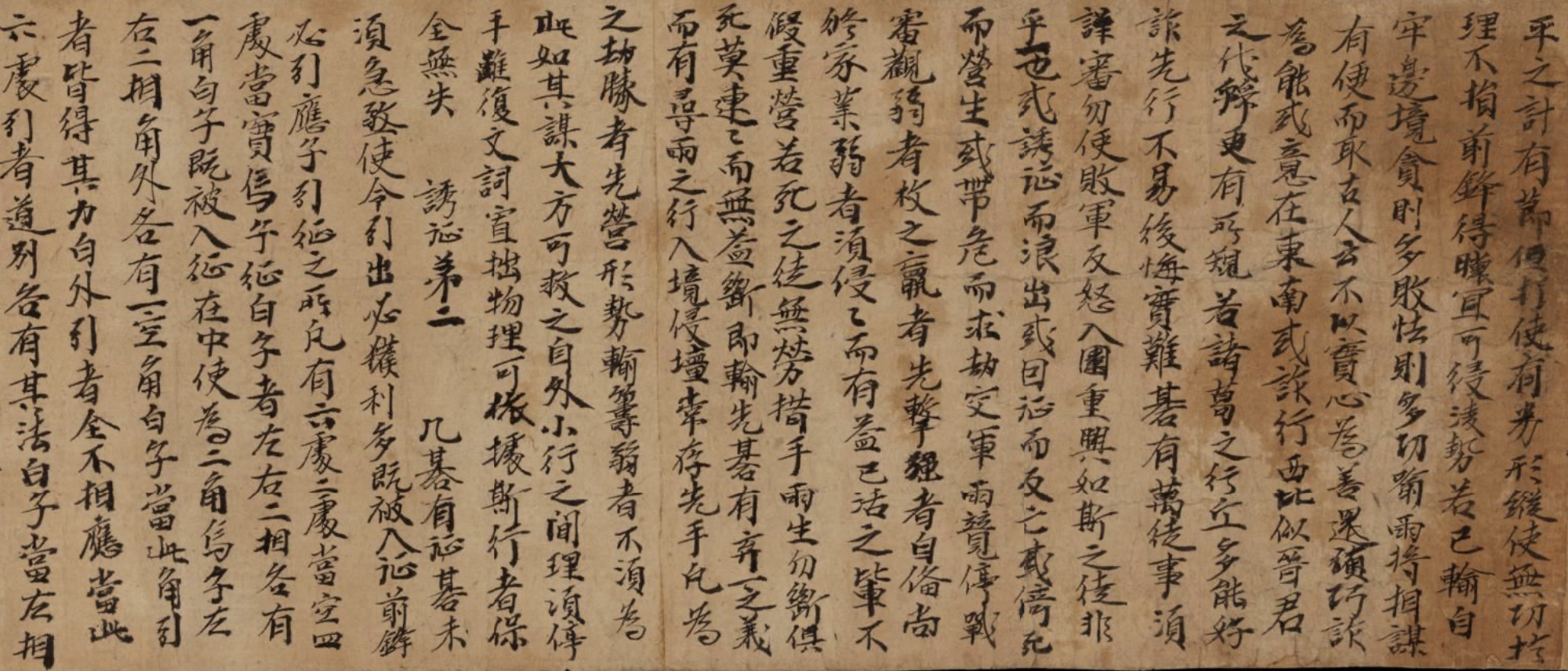

The non-clerical literature found in the Mogao Caves includes high-standing literature of famous writers (like those poems collected as a supplement to the whole Tang poems Quantangshi 全唐詩, or the private writings of many officials serving in the region of Dunhuang). Yet the most essential part is a kind of popular literature written in a sort of vernacular language used during the Tang period. It includes the literary genres of poetry, songs (geci 歌辭, shige 詩歌), Buddhist "stories of change" (bianwen 變文), proto-novellas (huaben xiaoshuo 話本小説) and rhapsodies or prose-poetry (fu 賦). The literature found in Dunhuang reveals many cultural and social aspects of that region during the Tang period, and it is a fascinating blend of various literary styles. The poems found among the treasure of Dunhuang literature are mainly of a type that was to be sung. Scholars in that field discern two different types, the grand da quci 大曲辭 and the lesser quzi ci 曲子辭 (also 曲子詞). The most significant part of these songs was written by authors from among the people and not by famous poets. The poems show a wide range of thoughts, wishes and feelings of the ordinary people. The poems employ personification, exaggeration, and parable. Buddhist literature exerted a significant influence on the Dunhuang poems. Collections of Dunhuang poetry have been published by Wang Zhongmin 王重民 (Dunhuang quzi ci ji 敦煌曲子辭集, 1950), Ren Erbei 任二北 (Dunhuang qu jiaolu 敦煌曲校錄, 1955), and Dunhuang geci ji 敦煌歌辭集/Dunhuang geci zongbian 敦煌歌辭總編, 1987), and Rao Zongyi 饒宗頤 (Dunhuang qu 敦煌曲, 1971).

The "stories of change" or "transformation texts" (bianwen) are a very unique genre in the history of Chinese literature. These stories were openly narrated in a mixture of prose and song by professional storytellers. They originated in the attempt of monasteries to attract a wider audience. For this purpose, the performers adapted older forms of public performances like the popular yuefu 樂府 songs, novellas or narrative rhapsodies. The language of the bianwen stories is a vernacular Chinese. The content of the stories first included stories of the Buddha's life that were used to propagate Buddhism, but later, non-Buddhist stories, mainly historical stories, were also narrated in a similar style. These were the forerunners of the early romances that were narrated to a public and not yet written down for individual reading. The finds of huaben novellas in Duhuang demonstrated that this genre already existed well before the Song period. The orally performed novellas found in Dunhuang, such as Tang Tanzong ru ming ji 唐太宗入冥記, Qiuhu 秋虎, Han qin hu huaben 韓擒虎話本 or Kongzi Xiang Tuo xiang wen shu 孔子項托相問書, were influenced by the "fantastic stories" (chuanqi 傳奇), and the latter also show features of the orally performed huaben stories. To meet the taste of the audience, the language of the huaben stories was very plain and direct. The most important publication about this genre is Dunhuang bianwen ji 敦煌變文集, published in 1957 by Wang Zhongmin (1903-1975), et al.

|

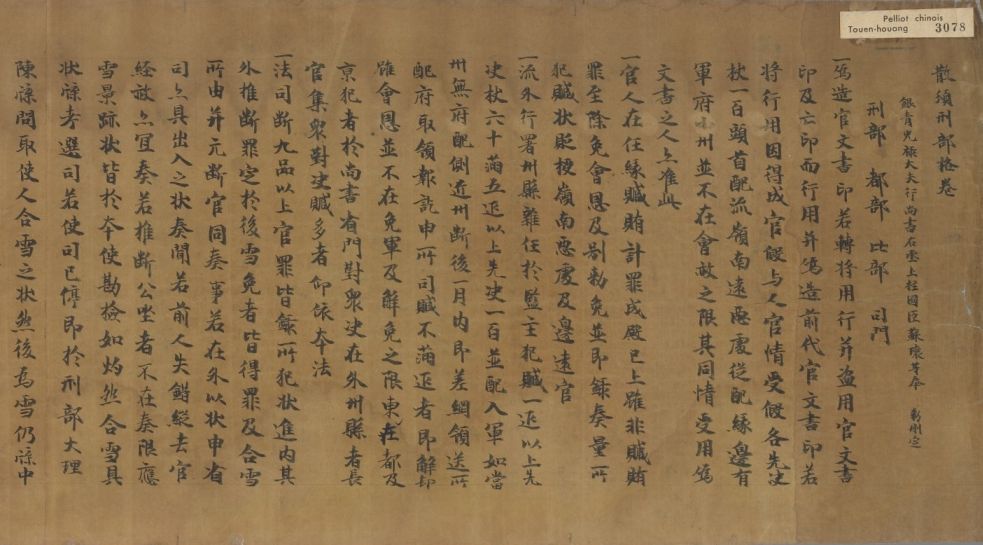

Beginning of the Shenlong sanban xingbu ge 神龍散頒刑部格 (Pelliot chinois 3078 散頒刑部格卷 [Li chan wen 禮懺文]), Gallica.bnf.fr. |

|

Beginning of the surviving fragment of the Dunhuang Qijing 敦煌碁經 (Or.8210/S.5574), International Dunhuang Programme. |

A few books are fragments of commentaries on Confucian Classics. More important than these is a fragment of Lu Fayan's 陸法言 (6th cent.) dictionary Qieyun 切韻 from the Tang period. Significant are the findings of Tang-period legal texts, like a commented version of the Tang Code Tanglü shuyi 唐律疏義, the Gong shi ling 公式令, Shenlong sanban xingbu ge 神龍散頒刑部格 or Shuibu shi 水部式. The Dunhuang documents also include Kong Yan's 孔衍 (268-320) Chunqiu houyu 春秋後語 and Cai Mo's 蔡謨 (281-356) commentary on the Hanshu 漢書. Geographical treatises like Huichao wang Wu Tianzhu guo zhuan 慧超往五天竺國傳 or Shazhou dudufu tujing 沙州都督府圖經 or family registers like Xinji tianxia xingwang shizu pu 新集天下姓望氏族譜 provide essential information about the local administration of the Tang empire and its relation with the Central and Southern Asian countries.

The documents of the local administration (the so-called guanwenshu 官文書) or of the administration of the monasteries are not to be forgotten. They include household registers, tax registers, reports about corvée labour, reports about the military colonies, the administrative units and the military garrison of Dunhuang. Another type of document are the so-called siwenshu 私文書, private documents with semi-official character, like property or assets, loan contracts or contracts about land-leasing or labour contracts, diaries, offering lists, or testaments.

Dunhuang and its culture are so important for the field of Chinese history that Chinese historians established the field of Dunhuang Studies (Dunhuangxue 敦煌學).